I finally found the reference I remembered, explaining what I’d encountered in that poem form I completely stole and probably misused on Sunday. What I was looking for was my links re alliterative verse.

A long line is divided into two half-lines. Half-lines are also known as ‘verses’, ‘hemistichs’, or ‘distichs’; the first is called the ‘a-verse’ (or ‘on-verse’), the second the ‘b-verse’ (or ‘off-verse’).[b] The rhythm of the b-verse is generally more regular than that of the a-verse, helping listeners to perceive where the end of the line falls.[1]

A heavy pause, or ‘cæsura‘, separates the verses.[1]

There was also this, which would have been useful the other day when NaPoWriMo’s prompt was about kennings:

The need to find an appropriate alliterating word gave certain other distinctive features to alliterative verse as well. Alliterative poets drew on a specialized vocabulary of poetic synonyms rarely used in prose texts and used standard images and metaphors called kennings.

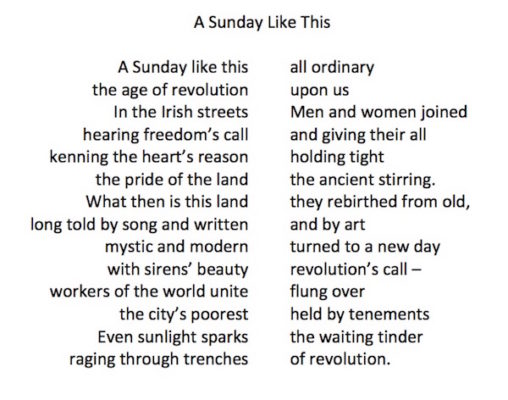

Turns out I could have properly showed you the poem with lines broken by || which is handy to know for future iterations, especially when trying to quote to unpredicably text-showing parts of the internet.

A Sunday like this || all ordinary

the age of revolution || upon us

Currently when I’m providing a two-line extract of a poem I try to put a • at the end of the first line, just in case whatever is showing it doesn’t honor the return that really is there. Hey it happens. Anyway, I had some fun melting a whole lot of stuff into a block of words with a river of space through the middle of it. And now I will try to remember and grasp more completely what the form should embrace.

WOW

wonderful.